I don't know why this plane crashed -- the NTSB will provide a report soon enough. So the following is not speculation on the cause of this crash.

But the conditions yesterday caused me to think about wind, and its contribution in other crashes.

Too many airplane accidents are caused by the pilot's inadequate accommodation for wind. Sure, all private pilots do some crosswind takeoffs and landing. But the practical and knowledge exams are content with the wind's effects on those short phases of flight. After all, once we're airborne we're part of the moving mass of air and that's that, right?

Not always.

Wind and Terrain

Throughout much of the Midwest, Great Plains, Great Lakes region, and Atlantic coast, the wind is basically unimpeded by terrain. Most turbulence we experience in our GA singles in these areas is caused by mixing between the low lying, slow-moving air near the ground and the faster-moving flow above or by wind flow disturbed by objects on the ground (trees, buildings, small hills).

In the Mountain west, pilots learn to study and scrutinize the winds before launching. Many GA single fliers won't launch if winds exceed 25 knots, since the downflow on the lee side of a mountain may exceed the climb rate of the airplane.

But terrain in the East can impose significant changes to the wind's direction and velocity. The Alleghenies are just west of here and I've flown over them many times. When winds are 10-20 knots from the west it will likely be a rough ride down low.. The same speed from the east may induce severe turbulence. Southerly or northerly flows don't result in much trouble, as the winds flow along the ridges.

Wind and Airplanes

The day of my CFI Checkride I planned to fly an A36 Bonanza from Connellsville (KVVS) to Rostraver (KFWQ) a short flight I'd made many times before. The skies were overcast and the wind was strong.

Here's an extract from a post about that flight:

I arrived at VVS to find the winds from 150 at 22 G 37. The winds died down a bit as I tried to decide what to do (only gusting to 32 knots), but were variable between 150-170. The wind sock seemed to favor 170, and after thinking it over I realized if I took off on 14 I would be climbing into all the turbulence off the mountains, and the sink rate might exceed my climb rate. So I opted to accept the 60 degree crosswind and take off from 23 and turn west as soon as possible.

The takeoff run was exciting -- I lined up on the left side to account for any drift. The airplane wanted to weathervane left into the wind but I worked hard at maintaining a track parallel to centerline. I reached 70 KIAS, held it on a bit longer, and popped up into the climb. The stall horn beeped at me a few times as I reached Vy (96 KIAS).

The crab angle to maintain runway centerline was about 30 degrees. I pitched and trimmed for 100 KIAS and left the gear down for stability. The airplane was caught several times by some sharp gusts and tried to roll but I was prepared and caught it and prevented the roll without over-correcting.

About 1200' AGL I raised the gear and began a slow turn westward at about 10 degree bank. If I banked more than that the winds rolling off the ridge were threatening to roll me right over, so I kept it gentle as I came around. The turbulence on climb out would have to rated moderate to severe. At 3500' MSL I leveled off. The turbulence was far less violent and the airplane was flying normally.

I don't have any expertise in heavy TW airplanes such as the DC-3, Beech Staggerwing, or B-17. I have some experience in a Cessna 180, Cub, and TaylorCraft L-4. I now have significant time in an Aeronca Chief which is a very light high-wing tailwheel. The wing loading on this airplane is on the order of 12lbs/Sqfoot which means the lightest gusts will affect the wing.

In winds above 20 knots on the ground, takeoff and landing becomes too much like work. Winds which would only make me decided which runway to take in the Bonanza or C205 will keep me grounded if I have a choice. Sometimes I don't and I launch in gusty winds anyway. It's a bit of a wrestling match until I get to an altitude where the terrain eddies are no longer the main cause of turbulence.

When penetrating turbulence in the Chief I slow down to 70 and just guide the airplane back to wings level. It makes no sense to grab the airplane from a left wing drop when a right wing drop is coming anyway. I also allow for some altitude deviations. I don't have a VSI but I do have a fairly good altimeter which lets me know when I've gained or lost 50 feet.

In winds above 20 knots on the ground, takeoff and landing becomes too much like work. Winds which would only make me decided which runway to take in the Bonanza or C205 will keep me grounded if I have a choice. Sometimes I don't and I launch in gusty winds anyway. It's a bit of a wrestling match until I get to an altitude where the terrain eddies are no longer the main cause of turbulence.

When penetrating turbulence in the Chief I slow down to 70 and just guide the airplane back to wings level. It makes no sense to grab the airplane from a left wing drop when a right wing drop is coming anyway. I also allow for some altitude deviations. I don't have a VSI but I do have a fairly good altimeter which lets me know when I've gained or lost 50 feet.

Wind and Forecasts

Here's my usual sequence when planning to fly local, on the same day (I use a different process for IFR or long XC flights):

- Day before flying: Check weather on http://aviationweather.gov/. First I look at the Prog Charts which will show fronts, boundaries, pressure gradients and areas of precipitation. I may end with the progs if it looks really good or really bad. For more information I look at winds aloft, then TAFS around the area I will be flying (Since my base is now S37, I use KRDG, KLNS, and KMDT. If all three are similar I have a greater confidence in the forecast. If not, I'm wary

- Pre-flight: I'm a morning flier. Winds are lighter, airports less busy, air cooler and less bumpy. In this part of Pennsylvania southerly flows suggest an impending change for the worse while northerly flows bring improvement. Westerlies are usually sign of at least 24 hours of good flying.

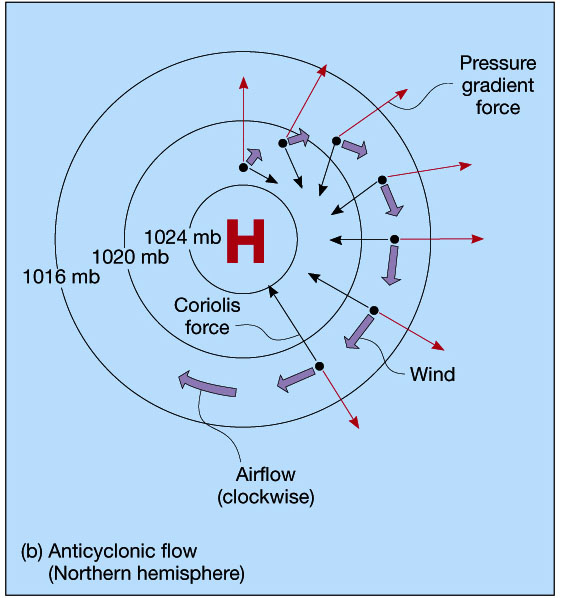

All this relates to the cyclonic flow of High Pressure systems. Good discussion here:

|

| Cyclonic flow of High pressure system |

If I'm going to fly cross country I call Flight service on the way to the airport. This call confirms what I know, but is an "official" weather brief and worth a second opinion if there is any ambiguity. If I'm going out and back ont he same day I'll get a standard brief for departure and then an outlook for return.I also check the FAA's NOTAM site for NOTAMS that may affect the flight.

Here's a good document to review if you need help with te whole weather briefing thing: http://www.eaa.org/chapters/resources/articles/0907_weather_briefing.pdf

Satisfied that the weather is VFR and flyable, I pull out the Chief and preflight and start.

Wind and Observations

Smoketown doesn't have an ASOS/AWOS, sSo we listen to the Lancaster Airport ASOS on 125.675. I usually call it on the way in (717) 569-886. That's all fine, but what I care about just before launch is what the wind is actually doing. This is where you almost have to forget about what you heard and replace it with what you can see and feel. If LNS ASOS reported "winds 090 at 5" I'll keep that in mind as I taxi out. But once I can see the windsocks (there are two at S37) I forget about the report. It's not unusual for Lancaster to report winds that are opposite of what's happening on the ground 5 miles away in Smoketown.

This ability to distrust is critical. Too often pilots press on to a specific runway because of what they heard, what what is actually happening is different. This may not be a problem on takeoff, but in a lightweight taildragger landing with a tailwind could result in significant heartache and expense.

How can you know what the wind is actually doing?

The same is true of winds at altitude. It's also not unusual for the winds to be blowing hard from the west or south 800' AGL while it's calm or light and variable on the ground. Ignoring this causes all sorts of problems. One night flying out of Connellsville (KVVS) I learned this lesson the hard way:

This is why sloppy flying is so dangerous. If you don't maintain a heading you don't know what the winds are doing. If you don't know what the winds are doing at pattern altitude you can get into the situation just described.

The most dangerous pilot is the one who gets away with ignorance for a while. Eventually it will catch up, and sadly too many times passengers are involved.

This ability to distrust is critical. Too often pilots press on to a specific runway because of what they heard, what what is actually happening is different. This may not be a problem on takeoff, but in a lightweight taildragger landing with a tailwind could result in significant heartache and expense.

How can you know what the wind is actually doing?

- Look at the windsocks

- Look at flags

- Observe the smoke or vapor from smokestacks. The larger ones will tell you what the wind is doing for a thousand feet up (if it goes straight up then bends 90 degrees in one direction, you know there is an inversion, with stable air below and a strong flow above).

- Look at ripples on a pond, lake, river

- Note the wind correction needed to maintain runway centerline and downwind, or fly along a road for a couple of miles.

The same is true of winds at altitude. It's also not unusual for the winds to be blowing hard from the west or south 800' AGL while it's calm or light and variable on the ground. Ignoring this causes all sorts of problems. One night flying out of Connellsville (KVVS) I learned this lesson the hard way:

"This evening the rather light winds were being reported as variable (all over, actually) by the AWOS. But what was really happening was that a very strong wind was blowing from the southeast very close to the ridge altitude (approximately 2500' MSL), and then rolling off the ridge line. So what VVS AWOS was sensing and reporting were the swirling eddie undercurrents (thus the generally west winds). The A36 is usually a very stable airplane, but in these conditions it was taking full control deflection to remain upright. I apologized to the passengers and told them we were heading back." (rest of the story here)The most deadly is the southwest or southerly flow for a pilot landing on a westerly runway (28 at Smoketown, for example).

So our pilot is flying along on base, ignoring the wind pushing him towards the runway. As he's abeam the numbers he sets up landing configuration and speed reduction.

A quick glance backward confirms the runway is at a 45 degree ange behind -- well, more than 45 -- ok, better turn...

So we throw in a normal 30 degree bank turn and then level off, look off the left wing -- Hey! I'm almost past the runway! And high, too. Hmmm..

| Base to final turn (from the Airplane Flying Handbook) |

So we need to get turned on runway heading right away! So the pilot banks the airplane over30 degrees. But he's configured for landing and slow now. He adds flaps: We're obviously high...

I'm gonna overshoot, he thinks, but he remembers being told not to exceed 30 degree banks in the pattern. But that rudder can slew the nose around towards the runway...

At the same time the airplane gets jostled about in the turbulent boundary layer between the strong southerly flow at 700' AGL and the calm, cooler air below.

So we're slow, banked, in a skid, and the airflow gets disturbed by a sudden, strong gust. The pilot instinctively pulls back and turns opposite to pick up the dropped wing...

A month later the NTSB narrative concludes the cause was "The pilot's failure to maintain adequate airspeed while maneuvering, which resulted in an aerodynamic stall."So how do we prevent this? First, know the winds, at the surface and at altitude. Winds aloft at 12,000 may be of no interest to you in a Cessna 152, but winds at 1200' better be. The lowest winds aloft report and forecast is 3,000. So it's up to us flying down low to understand what the wind is actually doing by how our airplane is affected. This doesn't take long and can be assessed in the pattern. If you need to crab right to maintain a track parallel to Runway 27 you know there's a southerly flow.

This is why sloppy flying is so dangerous. If you don't maintain a heading you don't know what the winds are doing. If you don't know what the winds are doing at pattern altitude you can get into the situation just described.

A reconstruction of an fatal Cirrus accident in 2008 by AvWeb:

The most dangerous pilot is the one who gets away with ignorance for a while. Eventually it will catch up, and sadly too many times passengers are involved.

Wind and Pilots

Not every pilot needs to fly in surface winds above 20 knots. But every pilot should be able to handle 20 knots, even if all you do is cruise around the pattern on calm Saturday mornings. You need to keep your skills up. Weather changes, and there will come a day when you fly to a nearby airport diner, finish lunch, and find that the winds forecast to be light and variable all day are now 20 gusting to 26.

Some pilots fight turbulence every bump with gritty determination. Don't. This usually makes it worse. better to let the stable airplane restore itself, or simply nudge it back if it goes too far. This is flying with a light touch, and is enabled by god trimming technique.

Some pilots fight turbulence every bump with gritty determination. Don't. This usually makes it worse. better to let the stable airplane restore itself, or simply nudge it back if it goes too far. This is flying with a light touch, and is enabled by god trimming technique.

Take-Aways

- Wind is dynamic, observations are snapshots in time. Once you're on final forget to windsock and do whatever it takes to keep the airplane aligned with the runway -- unless you have a reason to align some other way. In that case, make the airplane go where it needs to go.

- Expect a reduction in crab angle as you descend.

- Hand on the throttle all the way down final through touchdown and rollout. Use power to manage altitude, pitch to maintain airspeed (Cranky CFI Note: debate all you want about this, but on final this is simple, correct, and makes sense)

- Release the death grip in turbulence. You're fighting the airplane and making it worse.

Resources

(In no particular order)

- Aviation Weather Workshops (Highly recommended, but it ain't free)

- Lockheed Martin Weather briefing Tip Sheet (help fly through the phone tree)

- GA Pilot Weather Decision Guide (Nice summary from the FAA)

- Ten Things Pilots should know about FSS (good summary of how to work most efficiently with the Flight briefing system)

- Aviation Weather (ADDS)

- AOPA Weather (For AOPA members only)

- Winter Weather Flying by the National Weather service (date interface, solid content)

- GA CFI Weather training (A very interesting study)

- Aviation Weather Services (The Official text produced by the FAA)

- Pilot's Guide to Mountain Flying (AOPA members only, but good summary resource)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for taking the time to comment!